Recently, I stumbled upon a post joking about the end of the

null pointer exceptions just by taking the null value from the next

Java release. Think about it: uncountable hours of debugging an critical bugs

in production code solved at last!

Nowadays null pointer exceptions and the dozens of variants of them exists

on most of the programming languages in use. All of them can be traced back

to their introduction by Tony Hoare1 in the 60s. This great man whose

ideas still permeate current programming apologized in 2009 for bringing to

life such a destructive language feature:

I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965. At that time, I was designing the first comprehensive type system for references in an object oriented language (ALGOL W). My goal was to ensure that all use of references should be absolutely safe, with checking performed automatically by the compiler. But I couldn’t resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.

But, why is this so harmful? In principle, being able to point to an object or, alternatively, nowhere seems very useful to represent optional elements or relationships.

The problem lies on the null pointer definition itself: it throws an

exception when dereferenced. That means that every access to a nullable

reference should be guarded with a null-check or being assumed not null.

When the number of nullable variables or arguments grows, a combinatory

explosion of null checks is needed. This also interacts poorly with code

not following the Law of Demeter like the following made-up snippet

based on true events:

Machine getMachineByIface(String iface, payload: ProvisionDescriptor) {

if (payload.getProvision() == null)

return null;

if (payload.getProvision().getMachineList() == null)

return null;

for (Machine machine: payload.getProvision().getMachineList()) {

if (iface.equals(machine.getIface()))

return machine;

}

}

return null;

}The amount of housekeeping grows with the size of the codebase and the number of developers in it as that forces you to adopt a more defensive approach. You can trust the references passed within a module as long as it is small enough to be in your head, but module boundaries tend to be littered with null checking.

This is also a very infectious disease as every nullable value that is passed, saved as attribute or used as parameter brings the nullability elsewhere.

It is difficult to put a number on the cost of the null pointer as Hoare did

with his billion dollars of pain but we can use an approximate and inaccurate

but informative approach: look at the percentage of conditionals spent in

null checking in publicly available code. For this purpose, the low-hanging

fruit is to take some of the most watched Java projects in Github

and look for the null keyword on their conditionals.

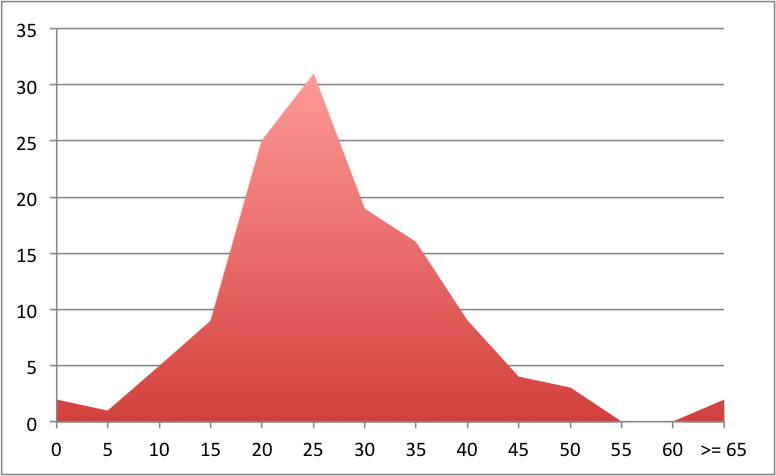

The results of applying this fast and dirty script to 126

repositories2 shows that the average percent of null-checking

conditionals or nullitis3 is 27% and it is distributed in a

familiar Gaussian way.

Number of projects by nullitis

That looks like a ton of accidental complexity4, you are supposed to be solving a problem instead of checking pointer references during a third of your time.

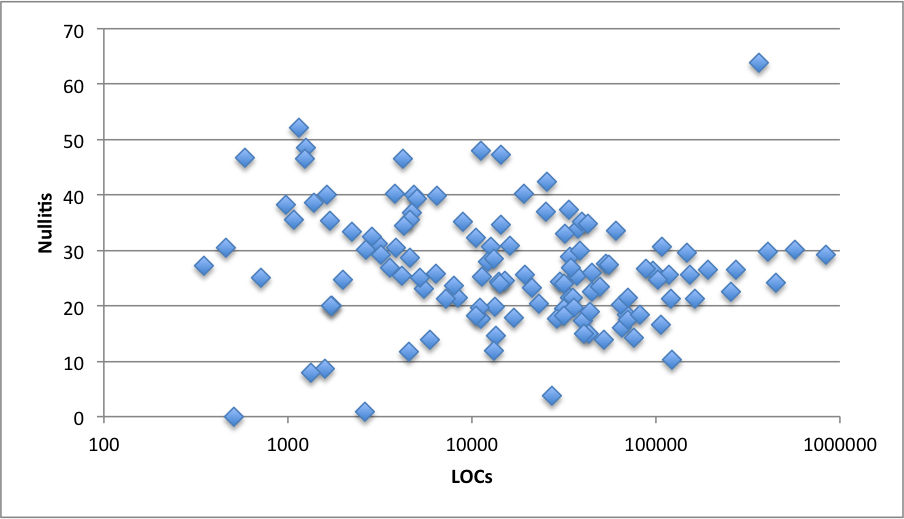

Nullitis vs LOC count

If we look at how this trend is distributed with respect to the size of the

repository measured on lines of code we can see that the mean is more or less

constant but the variance is very different for small and big projects (the

statistical term is heteroscedasticity). My interpretation is

that, in small projects you can cope with any amount of nullitis but, as the

codebase grows, the forces of having the logic buried on null checks on one

side and the need for defensive programming on the other prevent Java projects

for having much more or much less than a 30% of nullitis.

We can conclude that Tony Hoare fall short on his mind-child damage estimate as the software industry has hundreds of billions of dollars nowadays and that we need to sharp our tools to avoid this trap.

Let’s see in the upcoming posts (oop) what techniques we have to cope with this problem.

Update: a colleague of mine has pointed out that the varying variance can

be explained by the law of large numbers. If we assume finite variance

and some sort of statistical independence on the type of every conditional

line written (either a null-check or not) the averages will be closer and

closer to the population mean.

-

and he has a Turing award! ↩

-

I tried to get 128 but one of them has no Java code and had download ↩

-

Isn’t it great to made up words? ↩

-

Fred Brooks introduced this concept in his No silver bullet article as the complexity on a program that is not required by the problem to solve. Analogously, essential complexity comes as part of the problem. ↩